I was only planning to read female authors from my Classics Club list this year (since they’re having their Women’s Classic Literature event), but a recent film trailer took me back to Tarzan of the Apes (1912) by Edgar Rice Burroughs. When I first read Tarzan as a young teen, “with the noble poise of his handsome head upon those broad shoulders, and the fire of life and intelligence in those fine, clear eyes” he became one of my (many) literary crushes (Chapter XIII).

While he was “muscled as the best of the ancient Roman gladiators … yet with the soft and sinuous curves of a Greek god,” what impressed me most was that Tarzan taught himself to read from books he found in his human parents’ cabin. He could read and write fluent English by the age of 18, even though the only other language he had any experience with was the limited vocabulary of the fictive “anthropoid apes” who raised him. By the end of the book, he speaks fluent French as well. I consider myself reasonably intelligent, had the advantage of not being raised by apes, and I haven’t even managed to become bi-lingual.

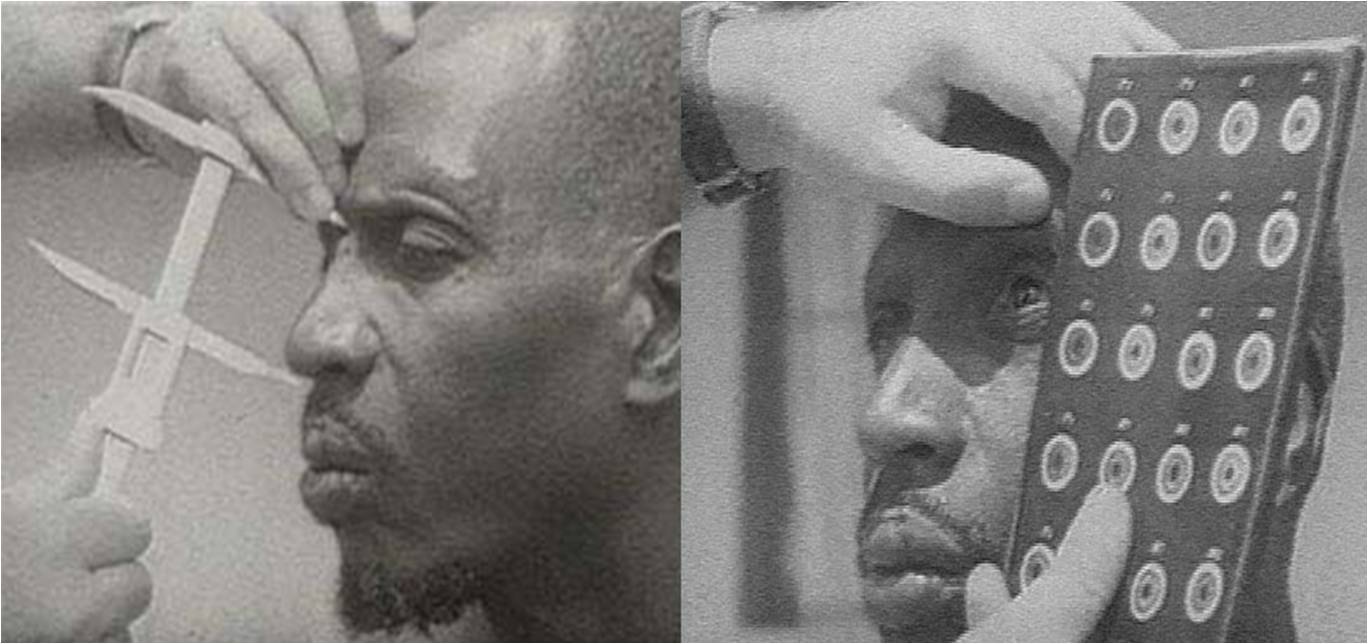

Yet shadowed by these descriptions of a super human Tarzan is a disturbing form of racism. Racism is evident from the moment the first black characters appear in the story, yet it goes far deeper than a matter of antiquated ideas about race popping up in the way a Classics author writes descriptions. Burroughs’ racism in Tarzan represents a mindset heavily influenced by evolutionary ideas about biology and race.

The “Brute Creatures” of Tarzan

On the back of my Penguin Classics edition, it says, “Tarzan of the Apes was part of a powerful Renaissance in the United States of popular interest in primitivism, born out of a complex reaction to the industrial revolution and Darwinism.” The introduction, written by John Seelye, describes Tarzan as “the image of a white man living with easy superiority among ferocious examples of brute creatures.” In the book, “brute creatures” doesn’t just include animals — it includes non-white people as well.

One place the idea of black inferiority shows up in Tarzan of the Apes is when an African tribe moves into Tarzan’s part of the jungle. Here’s the narrator’s first description:

In advance were fifty black warriors armed with slender wooden spears with ends hard baked over slow fires, and long bows and poisoned arrows. On their backs were oval shields, in their noses huge rings, while from the kinky wool of their heads protruded tufts of gay feathers.

Across their foreheads were tattooed three parallel lines of color, and on each breast three concentric circles. Their yellow teeth were filed to sharp points, and their great protruding lips added still further to the low and bestial brutishness of their appearance. (Chapter IX)

When Tarzan first sees a resident of this “bestial” and “brutish” village, he “looked with wonder upon the strange creature beneath him—so like him in form and yet so different in face and color. His books had portrayed the NEGRO, but how different had been the dull, dead print to this sleek thing of ebony, pulsing with life.” This warrior, Kulonga, is the first man Tarzan kills. He’s not the last.

Kulonga was killed to avenge Kala, Tarzan’s foster-mother. The other blacks who meet their death at Tarzan’s hand often do so arbitrarily — they crossed his path, he killed them. It doesn’t bother him any more than killing a lion or gorilla would. Nor does the narrative condemn him. These black “savages” are, after all, cannibals. Even Tarzan, a wild man raised by apes, shied away from eating Kulonga because his higher instincts trumped his habit of making a meal of any creature he killed. The only black characters who Tarzan does not consider “fair-game” are Jane’s heavily stereotyped companion Esmeralda and the residents of a Christianized village — in short, the ones who are associated with a white character.

Connecting Darwin to Racism

Seelye’s introduction notes that “Burroughs peddled an extreme line of racist goods” and that he was influenced by Darwinism, but does not connect the two. I think he should have, particularly in light of Darwin’s own writings on different races:

At some future period, not very distant as measured by centuries, the civilised races of man will almost certainly exterminate, and replace, the savage races throughout the world. At the same time the anthropomorphous apes . . . will no doubt be exterminated. The break between man and his nearest allies will then be wider, for it will intervene between man in a more civilised state, as we may hope, even than the Caucasian, and some ape as low as a baboon, instead of as now between the negro or Australian and the gorilla.” — Charles Darwin, from The Descent of Man

A movement based on these ideas, known as Social Dawrinism, had a strong foothold by the late 1800s and was undoubtedly familiar to Burroughs when he wrote Tarzan of the Apes. In keeping with the Darwinian idea that the Caucasian is the superior race, we see Tarzan rise high above his anthropoid companions based solely on his human reason and the superior blood of an English gentleman.

Though true stories of feral children don’t seem to support the idea that a human raised by animals would self-educate, I’m willing to concede that Tarzan could reach a higher level than the apes. Christianity teaches man was created for a purpose, and I believe humans are a higher sort of creature than animals. What I cannot get behind is the idea that some “types” of humans are higher than others, and yet this is the very idea Darwin’s supporters and Burroughs were pushing.

Social Darwinism was, and is, one of the most disturbing side-effects to evolutionary ideas. Quoting from an article on Racism Review, “By the late 1800s a racist perspective called ‘social Darwinism’ extensively developed these ideas of Darwin and argued aggressively that certain “inferior races” were less evolved, less human, and more apelike than the “superior races.” Darwin himself was anti-slavery, but he did nothing to counter the ideas of white superiority and even racial extermination inherent to social Darwinism. You’re unlikely to hear someone today come right out and say something like “blacks are inherently inferior because they are more closely related to apes,” but the ideas of social Darwinism still persist today in stereotypes such as “black men are better athletes” or “black women are sexually promiscuous.”

Burroughs vs. Bible

Yuck — I feel icky just typing about aspects of social Darwinism. I’m not claiming I’ve achieved color-blindness or that I’m as free of prejudice as I’d like, but I prefer to assume we all belong to the “human race” (race being a social construct loosely based on biology) and focus on ethnicity (which is associated with culture) when discussing differences between human groups. Honestly, when I think about different races the first thing that comes to mind is things like Vulcans, Twi’leks, and humans. Being an avid sci-fi fan has given me a different perspective on the idea of “race.” And so has being a Christian.

God, who made the world and everything in it, since He is Lord of heaven and earth, does not dwell in temples made with hands. Nor is He worshiped with men’s hands, as though He needed anything, since He gives to all life, breath, and all things. And He has made from one blood every nation of men to dwell on all the face of the earth, and has determined their preappointed times and the boundaries of their dwellings, so that they should seek the Lord, in the hope that they might grope for Him and find Him, though He is not far from each one of us; for in Him we live and move and have our being, as also some of your own poets have said, ‘For we are also His offspring.’ (Acts 17:24-28)

While people have historically twisted the scriptures to make an argument for racisim, “God shows no partiality. But in every nation whoever fears Him and works righteousness is accepted by Him” (Acts 10:34-35). God doesn’t care about skin tone or ethnicity. He cares about the state of your heart and relationship to Him and His people.

Burroughs, however, implies your heart is inherently good if you’re a white man. In the version of Africa Burroughs’ presents, the primitive conditions provide a showcase for man in his most natural state uncorrupted by softening civilization. For Tarzan — the white man isolated from other humans — his natural state is inherently noble. Black characters in the same location, however, are portrayed little better (and sometimes worse) than the animals in Tarzan’s jungle.

There are aspects of the Tarzan story I enjoyed, but I think the best part of re-reading this book was how deeply it made me think. I know there are some people who advise against reading books that contain racist, sexist or otherwise unpopular themes because they’re uncomfortable or offensive. I would counter that’s precisely why we need to read books like this. Racism exists, and pretending it doesn’t won’t make it go away. Engaging with it and understanding the historical motivation of these ideas is a first step toward countering racist dogma, deconstructing misconceptions, and learning to live in peace.

Click here to get a copy of Tarzan of the Apes. Please note that this is an affiliate link. This means that, at no additional cost to you, I will receive a commission if you click on the link and make a purchase.